On June 21, 2015, 30 people gathered in a session called “Generating Shared Principles for Design Justice” at the Allied Media Conference in Detroit. The participants identified as designers, artists, technologists, and community organizers.

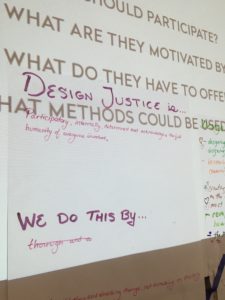

Participants discussing a design for social impact story

The hope was to start shaping a shared definition of “design justice” — as distinguished from “design for social impact” or “design for good”, which are well intentioned but because they are not driven by principles of justice can be harmful, exclusionary, and can perpetuate the systems and structures that give rise to the need for design interventions in the first place. How could we redesign design so that those who are normally marginalized by it, those who are characterized as passive beneficiaries of design thinking, become co-creators of solutions, of futures?

We began by breaking out into groups, with each group examining one of three design for social impact stories that had recently come out of Detroit: the EMPWR Coat, a winter coat that converts into a sleeping bag for the city’s homeless; Shinola, a luxury watch company that proudly employs Detroiters, and Detroit Future City, a non-profit economic development organization. These stories had received a great deal of positive attention in design and business press as socially engaged projects.

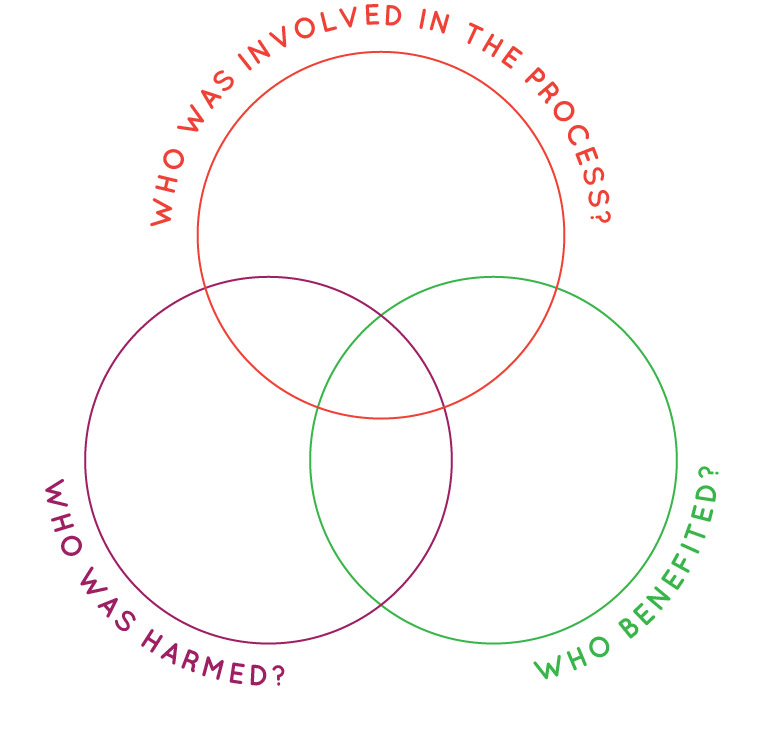

Using a venn diagram, we plotted out the characters in these stories — who was involved in the design process? Who was harmed by the product or in the process? And who benefited?

When the groups reported back, we found that some people who benefited and were also harmed; in the case of the EMPWR coat, homeless Detroiters received a warm garment in the short term, but in creating a “solution” that kept homeless people on the street, it created a business opportunity for the designer while doing little to end the social dynamics that give rise to homelessness.

We also found that those who were harmed were not involved, or only minimally involved in the design processes. Designing “for” and not “with” meant that community resources, knowledge and creativity were not activated, that the designers might benefit more than the community the solution was meant to serve, and that problems weren’t actually solved.

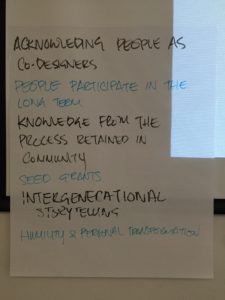

Notes from the report back discussion

The participants then discussed how the design process might be re-imagined so that design could support communities and social justice. Each group looked at a different stage of the design process (problem definition, research, conceptual exploration, development, delivery, and evaluation) and discussed how to re-shape it so that the work was driven by the community.

Defining Design Justice

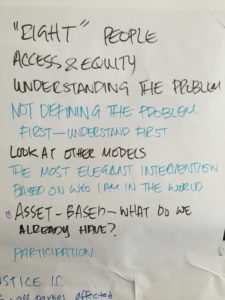

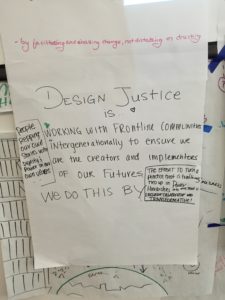

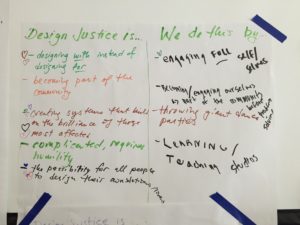

From these discussions, participants were asked to respond to two prompts: “Design justice is…” and “We do this by…”

Here are the compiled and edited responses:

Design Justice is:

- Working with frontline communities intergenerationally to ensure we are the creators and implementors of our futures

- The effort to turn a practice that is traditionally tied up in power hierarchies into one that is inclusive, collaborative, and transformative

- Participatory, internally determined and acknowledges the full humanity of everyone involved

- Designing with instead of for

- Becoming part of the community

- Creating systems that build on the brilliance of those most affected

- Complicated and requires humility

- The possibility for all people to design their own solutions and lives

- Fluid understanding

- The collapse of power relationships in conventional design processes

- Planning done by the community, for the community

- Bringing together healing justice, transformative justice, and economic justice to frame design justice

- Considering those directly and indirectly impacted

- Non-extractive

- Connecting with the earth

- Drawing on old wisdom while innovating new solutions that fit the needs of those most impacted

We do this by and through:

- Intergenerational storytelling

- Humility and personal transformation

- Representing our own stories with dignity and power in our own voices

- Facilitating and enabling change rather than dictating or directing

- Engaging our full selves

- Becoming/engaging ourselves as part of the community before problem solving

- Throwing giant dance parties

- Learning/teaching studios

- Seeking existing resources and strategies at the margins

- Participation

- Transparency

- Sustained engagement

- Creating community ownership of design products & processes

This session was just the beginning of what will hopefully be a long and rich conversation on how design can better support communities facing injustice. In a future post we will explore how we have tried to apply these principles.

This session was inspired by the Allied Media Projects (AMP) Network Principles and Detroit Future Youth’s story-building activities. It was developed by Una Lee, Jenny Lee, and Melissa Moore and presented by Una Lee and Wesley Taylor. The principles were written by: Melissa Moore, Shauen Pearce, Ginger Brooks Takahashi, Ebony Dumas, Heather Posten, Kristyn Sonnenberg, Sam Holleran, Ryan Hayes, Dan Herrle, Dawn Walker, Tina Hanaé Miller, Nikki Roach, Aylwin Lo, Noelle Barber, Kiwi Illafonte, Devon De Lená, Ash Arder, Brooke Toczylowski, Kristina Miller, Nancy Meza, Becca Budde, Marina Csomor, Paige Reitz, Leslie Stem, Walter Wilson, Gina Reichert, and Danny Spitzberg.

—————————————-

Jun 30, 2016

Design Justice Jam: Poster Design Workshop

The Poster Design Workshop held on June 2, 2016 at the Centre for Social Innovation in Regent Park brought together community members across Toronto for an evening of community-centred poster designing. Co-facilitators Una Lee and Gracen Brilmyer walked participants through the essentials of poster design — text, imagery and layout — as they created posters individually and in groups that brought awareness to local issues.

Using imagery from the Vision Archive, participants created posters that represented and brought awareness to a multiplicity of issues such as solidarity with Latin America, environmental justice in the Grassy Narrows community in Ontario, welcoming refugees, self-care, and basic income.

Una and Gracen are fellows with the Centre for Technology, Society and Policy at the University of Berkeley for the Vision Archive. The Poster Design workshop was part of a series of workshops to be delivered as part of this fellowship. The Vision Archive’s design jams are a key part of the fellowship project. These 3-hour sessions connect artists with activists, provide concrete design skills, and result in new and remixed content that is then uploaded to the site.

About the Vision Archive:

The Vision Archive was conceived in 2014 by Una Lee. As a designer working within social movements, she was concerned by some of the trends she was noticing in movement imagery. On the one hand, clipart of raised fists and barbed wire had become visual shorthand for community organizing. On the other hand, some organizations were leaning towards more a more “professional” i.e. bland aesthetic in the hopes of seeming more credible to funders. She worried that these two types of aesthetics were contributing to disengagement from movements.

Knowing that what we see shapes what we believe is possible, Una felt a need to intervene and make an intentional effort to shift the visual culture of social movements. What if social movement imagery were visionary in addition to being critical? And what if it were created by organizers and community members to reflect the world they are working towards?

In May 2014, Una led the first “design justice jam” and through a series of participatory activities facilitated 24 activists and artists in the creation of the first set of visionary icons. In the summer of 2015, Una teamed up with designer/scholar Gracen Brilmyer, front end developer Jeff Debutte, and backend developer Alex Leitch to build visionarchive.io.